Planning for Four Years of College

Find your degree

By Jennifer W. Eisenberg

No shortage of advice is offered for the pre-freshman who is feeling overwhelmed. College is simply not as rare an option as it used to be. Right now, less than half the eligible population has completed a bachelor’s degree, yet it is strongly recommended that you get into and complete a four year degree, and a chief reason is that just in raw statistics the earning power is hard to achieve any other way. Over 60% of Americans have at least some college. The pressure of heavy emphasis and the difficulty to manage BA or BS in less than five years, especially if you are the first in your family to go to college. All kinds of training and assistance can help, but probably the best thing you can do is create a plan, or a few plans, to realistically assess what you need to get that paper.

A plan is a five step process: setting your goals; developing your approach to goal achievement; defining which activities will help you achieve the goals; prioritizing those activities; and putting those goals to a tentative schedule. When making a four year plan for college, some of these steps are more obvious than others. Obviously, the goal is to graduate from college. Obviously, the timeline is roughly four years. The steps in between these two can be a little less clear. One of the activities which will help you achieve the worthwhile goal of matriculation is the creation of a four year plan during your first days as a college student. Following the four year plan as closely as possible (life happens) should be on your list of priorities.

You may also like:

- Planning for your First Year in College

- Planning for Graduate School as an Undergrad

- College Planning Quick Checklist

- College Planning Guide

- 10 Useful College Planning Apps

Why do you need a four year plan?

A four year plan is not generally required as a part of your freshman year, i.e., you won’t get a grade on it, but this document is a road map of your path through college, illustrating which courses follow which and what you can expect out of your course load term by term. Your school probably has their own particular ideation on this form, either as a piece of paper you fill out during orientation or as a digital form to be filled out virtually. You will need access to your major’s section of the college catalog to fill out this form and then you will go over it with your advisor as your register the first time.

Most universities provide year-by-year calendars with dates to register and how limited or intermittent certain offerings may be. It’s obviously worth your time to take advantage of the tools that have grown more student-friendly. More informal (former student) sources can provide anecdata on how to do more than just survive.

Most schools also have a pre-first-year program meant to acclimate you to undergraduate life. Conventionally, the first year is to get used to college and get through it. More than a quarter of the freshmen who enter when you do will drop before sophomore year. Most of these programs provide a typical classroom and lecture hall experience over the course of a week or more. Among the things you will have to do will likely be to put together an eight-semester plan. Drawing up such a plan can be a good technique if you are a visual learner. Seeing the progression of classes it will take to get to graduation, and referring back to it often over your college career, will keep you “bought in” to the process.

Year two will likely be the period where you will choose a major and minors. From this moment until that point, the four-year plans recommended here are probably going to feel abstract and disconnected from your actual experience. This is why the advice here comes from a range of sources, but you will be readier then to truly fill out the plan.

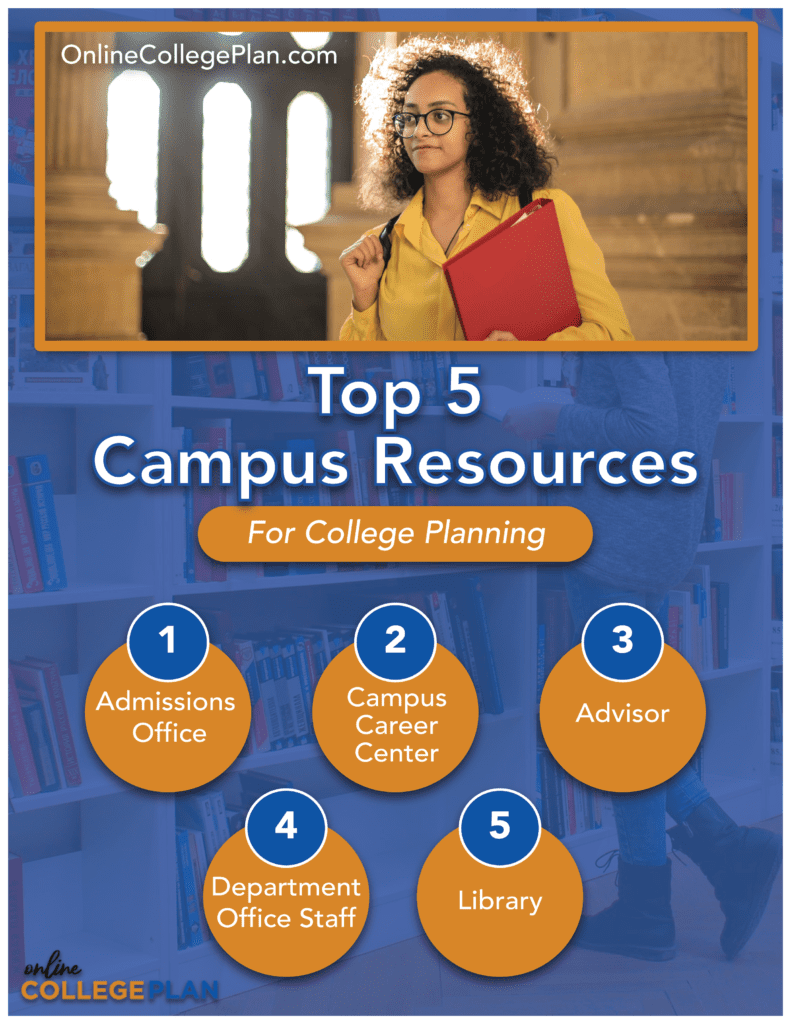

Admissions Office

You are a freshman in college, just moved into your dorm and ready to put your best foot forward academically. That will start with registration tomorrow, but what can you do to prepare for that, now? Your first stop is the admissions office, where you pick up a copy of the college catalog. Or the office of the college supporting your particular college which houses your department or discipline. This book will outline the basics in your search for what your major consists of and how your four years will be structured. It will also show you which courses will count towards which electives and which classes (however interesting) will be nothing but wasted time and money, from the standpoint of your major. You can even ask the staff of this office to help you best use the college catalog. This information is definitely available on your school’s website (if it is raining) and may be available on the school app. Another thing you can learn from the college catalog is the location of the department office for your particular field of study.

Department Office Staff

The staff of this office will probably be a mix of upperclassmen in this department and individuals on staff who are intimately familiar with the ins and outs of the department. Either way they are an excellent resource on how to get your particular focus into the generic template of the major laid out by the catalog. They will know what staff members share your interests or who can be counted on to offer excellent electives as well as which areas will make a good complementary minor or which crib course is best for that second semester of sophomore year when you (for example) have a science with a lab, a 200 level foreign language, a math and a total of 17 hours. There may even be one single person to answer all your questions, and you could probably recognize this person very easily — he or she is that one person who’s been there long enough to know the ins and outs but also has the backs of the neophyte students. This person is an invaluable resource for things like the real names for the student center and the physics building and whether to use public or school-sponsored transportation (or just to use Lyft).

Degree Advisor

Ideally, your degree advisor will be someone who shares your particular take on your chosen subject, but more likely it will be the junior faculty member tasked with registering people in your year with the letter your last name begins with. Nevertheless, try to make an ally of this person, for he or she will know someone who could write you a potential letter of recommendation for grad school or internships or potential employers in the future. Or your degree advisor may be the very person who will write your letter of rec. This is literally your first chance to make a good impression with the department. Remember to brush your teeth. When you arrive at this appointment, they will run over the expected courses for the first year, and you will probably roughly sketch out a plan for all four years. Maybe prep this list the night before, knowing which electives you would rather take, but leaving room for flexibility in case that class is not offered that particular term, or should a more interesting one arise. You will have a chance to review this four-year plan every semester so it is not a document etched in stone.

In any case, strong anecdotal evidence demonstrates that advisor ratings shoot up when students decide on their majors and get advice more attuned to their personal and academic needs. So there’s going to be a temptation to get into a major quickly, but you will likely have to bear with the reality of initial advising by someone in the admissions department if you do not come to college with a major selected. These individuals do know their stuff, but they work with arguably the largest population of a major (undeclared), so attempting to make an impression here is neither warranted nor advisable. Of course, be civil and of good will, but do not expect to add this person to your short list of prospective letter of reference writers, for example.

What if I Change My Major?

See above. Lather-rinse-repeat. The good news is that most programs require the same core competencies like a social science and so many foreign language credits as electives, so the less dramatic your major change and the earlier in your college career that you decide to pitch the old major, the more of your credits will transfer from program to program. The longer you are in school and the more specialized classwork you take, watch as those transferable credits winnow away, and you have only the dreaded “excess hours” remaining. If you are moving from a business field to, say an engineering one, some courses will transfer, but you may need to reconsider your math and science class choices as you might not meet the initial prerequisites.

As long as you are out and about strolling the campus, looking for ways to maximize your school time, I would suggest one final stop.

The Campus Career Center

This place is helpful to see what kind of job prospects are available in your chosen (or possible) career and also may offer vocational testing if you are unsure of your long-term college plans. This is a good locale to be familiar with, as they offer a number of services that will become mission-critical as you advance in class standing: resume review; cover letter proofing; mock interview practice; and they will also host periodic job fairs which give you facetime with recruiters for companies you may be interested in. Here is as good a place as any to mention that now is a good time to start building your master resume. This is a document you will pull from to make up individual resumes tailored to job applications, or just for putting your general best foot forward. The master resume is where you document every plaudit you receive, every accreditation you acquire, every publishing credit you accrue. All of this is fodder for the master resume

Most undergraduate programs are about 120-semester credits, sans labs, or other parallel credit situations. Your advisor probably will be most helpful in determining your likely credit loads per term, and how or how not to use those transfer credits. The current thinking at many schools is to intend to take at least 15 hours per term to continue to progress academically and graduate on time. Summer courses and internships may put a dent in this schedule in either direction and that is completely within the range of normal.

Since you are planning to plan, as it were, you might opt for multiple dream scenarios for your potential majors. Never has a plan ever gotten more than a few consecutive items correctly predicted and worked out, anyway. And making a four year plan for each potential major will give you an idea as to whether you can sustain interest in each topic as you visualize the course schedule and progression.

Having to face your own limitations is admirable and difficult. The truth is that there are strong odds you are overconfident in some of your skill sets and overly insecure in others. The college setting will test these areas fairly quickly. While unpleasant to face, these are better figured out sooner than later. How you handle these growing pains will determine whether this whole college thing is what you imagined. With a little grit and a little grace, you can come out of the college experience a well-rounded, fairly educated adult, ready to enter the workforce.

College is accomplished in a fairly predictable process, lowerclassmen to upperclassmen, undeclared major to graduate. Having an idea of how the process is constructed from the start, and revisiting that idea for possible redrafting as you progress is a smart idea that can save you time and money and a lot of grief, to be honest. We have tried to show you the benefits of constructing a four-year plan and viewing each year of your college experience as part of a whole journey that will take you from adolescence to adulthood. This list was meant to help college students and those who are bound for college to save valuable time and energy up front in their educational process. Our goal is the same as yours: to streamline the procedure of getting from post-secondary graduate to baccalaureate degree holder.